Diving into the past: Guest Post by Anna M. Weiss

By Lexi on October 22, 2018

Coral reefs are iconic ecosystems, and their decline due to climate change and other stressors such as overfishing and pollution will dramatically alter what reefs of the future will look like. Coral reefs provide a number of services to humans and the planet as a whole, and it is likely that the benefits we gain from coral reefs (reefs protect coastal communities from storms, benefit fishing and tourism industries, and harbor molecules that are potential treatments for ailments from arthiritis to cancer) will be fundamentally changed as a result of climate change.

In order to manage the reef ecosystems of the future and preserve these valuable resources we need to be able to predict what reefs will look like after years of degradation by human activity. While ecologists can only study modern reefs on time scales of days to decades, the fossil record provides millions of years of natural experiments in the interaction between climate and ecosystems. This is where I come in. I am studying reefs from 56 million years ago that experienced a climate change event that is similar to what we are experiencing today and can be considered a “worst case scenario” for the future. The interesting part, though, is that corals did not go extinct, even though the conditions they were living in were almost inhospitable. My goal is to understand why.

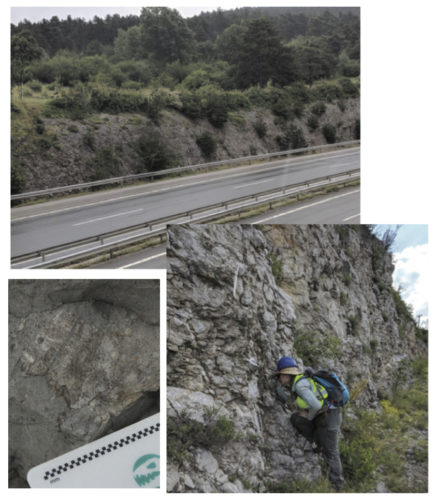

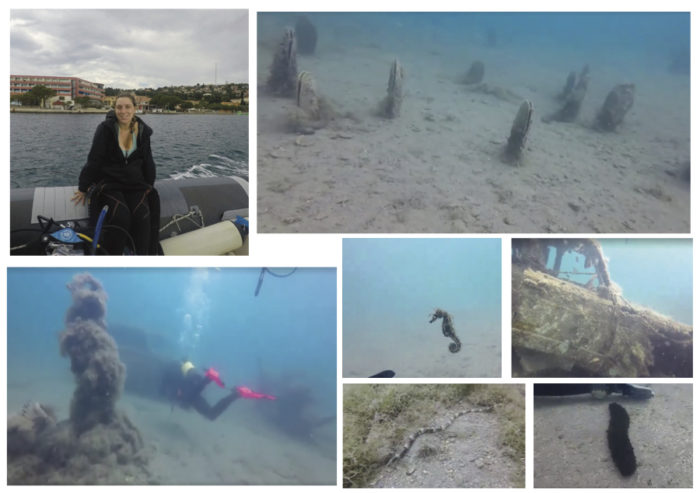

To do this, I flew to Slovenia, where a reef began to build almost 60 million years ago when sea level was much higher. Slovenia, my field area, (along with many other countries, including France, Germany, Spain, Egypt, and Iran) was submerged in a warm, shallow ocean that was covered with reef platforms (think of the Caribbean). Here a coral reef transitioned from coral-dominated to one made mostly of microbes (but still containing corals) over a period of several thousand years. Previous work I have done at this site makes me believe that this is due to increasing temperature destabilizing the ecosystem. This allowed microbes to take over as the dominant reef builders, and corals that could withstand high temperatures lived within the microbial framework. Eventually, when it got too hot, the reef completely collapsed. Millions of years later the fossilized reef is now high in the mountains, lining the side of the Slovenian motorway.

Bottom Right: A sea urchin fossil that is becoming exposed. Bottom Left: Getting up close and personal with the rocks.

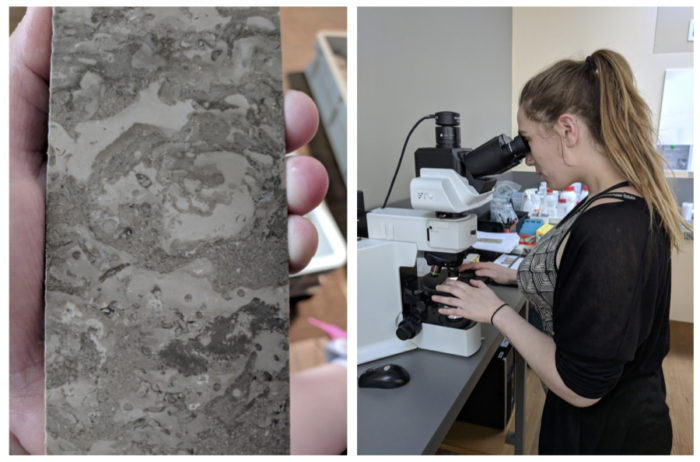

Now that I am back in Austin, I’m working on preparing samples for further analysis by cutting and nicely polishing the rocks. Next, I will quantify ecological change by counting the abundance of fossil taxa and analyzing them statistically. Previous work I have done has shown consistent ecological change in one geographic area, but the new data will show me what community change looks like across the broader reef system. The data from the cores will especially come in handy here, because it will show whether our previous findings are consistent with what we see elsewhere on the platform. I’m very excited about this project, because so far it is showing that corals and reefs may be more resilient to climate change than we previously thought. This doesn’t mean that we should stop caring about the fate of corals or assume they will be fine, but it does provide a ray of hope for the future of reefs if we act now.

As part of the 2018 Paleontological Society Student Research Grant competition, the Bearded Lady Project: Currano Scholarship Fund awarded their first student research grants. Thanks to all of our host venues who have offered movie screenings and the traveling exhibition, we were able to provide two women with funding to help support their field research. Anna M. Weiss was one of the two awardees.